In New Mexico, a bold experiment aims to take police out of the equation for mental health calls: The Washington Post

In New Mexico, a bold experiment aims to take police out of the equation for mental health calls: The Washington Post

ALBUQUERQUE — Elisha Lucero was known in her family as a painter, a fisherwoman and a caretaker who had put aside her ambitions to nurse relatives through bouts of poor health.

She was also gripped by mental illness, and on a summer’s night in 2019, the 28-year-old was behaving so erratically that a cousin called 911 from their suburban Albuquerque home. Sheriff’s deputies banged on the door and demanded that Lucero, who stood 4 feet 11 inches with her shoes on, come outside.

When she did, the deputies shot her 21 times.

While the circumstances remain disputed — authorities say Lucero rushed toward them with a knife, a claim her family denies — the case prompted questions over what would have happened had mental health professionals responded to that call and others like it, rather than armed officers.

Now Albuquerque is trying to find out.

In one of the most tangible shifts in public safety since last year’s killing of George Floyd

spawned anti-police-brutality protests nationwide, New Mexico’s largest city has established

a new category of first responder. Starting in September, 911 dispatchers had an option

beyond the police, with social workers and others in related fields patrolling the city and

fielding calls pertaining to mental health, substance abuse or homelessness that otherwise

would have been handled by an armed officer.

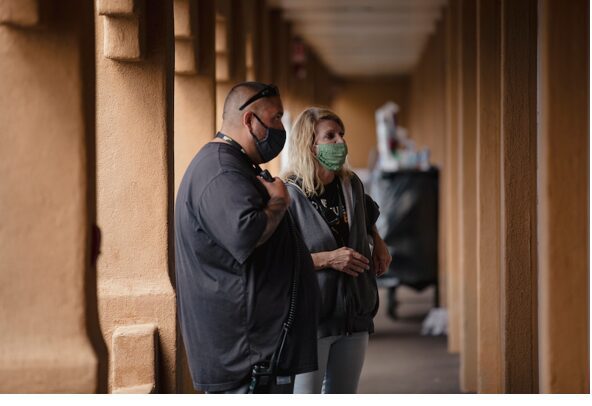

The contrast is vivid: The members of the freshly established Community Safety Department

sport T-shirts, lean heavily on their de-escalation training and emphasize that they’re not

there to enforce the law or make arrests. Instead, they fill the trunks of their Honda Accord

patrol cars with enticements designed to win the trust of the people they are seeking to help.

“We don’t have a badge and a gun,” Walter Adams said, after assisting a disoriented man

who was sprawled on the pavement outside a shuttered gas station one recent afternoon.

“We have water and snacks.”

Other cities watching

Whether the new department can make the desired impact is being closely watched not only

here, but also in cities nationwide that are either attempting or contemplating something

similar.

While many of the changes demanded by protesters in the wake of Floyd’s killing remain

unfulfilled — overall police budgets remain largely intact, along with rules that shield officers

from liability — the concept of shifting the burden of mental health calls to unarmed

responders continues to gain traction.

“We’re seeing it all over the place,” said Alex Vitale, coordinator of the Policing and Social

Justice Project at Brooklyn College.

The appeal is clear: In places where the idea has been tried, Vitale said, the outcome has

been “fewer emergency room visits, which are extremely expensive, fewer jailings, which are

even more expensive, and fewer police interventions, which come with a huge risk of force.”

Orlando’s mayor recently proclaimed “great results” from that city’s six-month pilot

program. Denver’s year-old approach also has yielded promising data and has become a

model being eyed by St. Louis and others. The best-established program is in Eugene, Ore.,

while major cities — including New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Washington — are

all in various stages of experimentation.

Unlike other reform ideas, this one has received a broadly warm reception from police

chiefs, who say it can relieve some of the responsibility from their overburdened officers at a

time when violent crime is rising.

Reform advocates, meanwhile, say it can make a substantial dent in the problem of police

brutality: Of the roughly 1,000 people killed by the police each year, more than a quarter

have been in the throes of a mental health crisis, according to a Washington Post database.

“This new department is proving its worth whether crime is skyrocketing or whether there

are issues around over-policing and racism in law enforcement,” said Albuquerque Mayor

Tim Keller. “It works at both those problems.”

Yet Keller, who spearheaded the creation of the Albuquerque Community Safety

Department, known as ACS, also acknowledges a risk. Unlike many other cities,

Albuquerque’s program is no tentative pilot: It’s a free-standing department, with a

multimillion-dollar budget and ambitions to hire hundreds of responders, field tens of

thousands of calls each year, and fundamentally reshape an emergency response system that

hasn’t been altered this significantly since EMTs were added half a century ago.

“This is literally changing the system. So, we’ll see. I think it’s going to work, but it might

not,” Keller said from his 11th-floor city hall office, with panoramic views of downtown and

the mountains that rise beyond. “You’ve got to be careful if you want to go down this path.”

Part of the reason for caution is that Albuquerque is struggling: The city of just over a halfmillion people faces surging levels of violent crime and homelessness. The murder rate

qualifies it as one of the most dangerous cities in the country.

“The streets of Albuquerque are rough,” said Shaun Willoughby, a police detective who

serves as president of the city’s officers’ union. “We are number one on every single bad list.

And we have been forever.”

Willoughby said he would like to be optimistic that social workers can achieve better

outcomes and take some of the burden off officers. But the reality, he said, is that unarmed

responders are putting themselves in peril operating in a city where weapons are so

pervasive and violence so common.

“We worry for these clinicians,” he said. “It’s all fun and games until you get on scene and

someone is wanting to fight.”

Reform advocates counter that police in Albuquerque have long contributed to the problem,

escalating situations that could have been defused with a lighter touch. The city’s police have

operated under federal monitoring since 2014, after investigators found a pattern of

excessive force — particularly when dealing with people suffering mental illness.

“This department has a long history of violence,” said Peter Simonson, executive director of

the ACLU of New Mexico. Lethal use of force by officers has declined under the federal

monitoring, he said, “but it could come back at any time.”

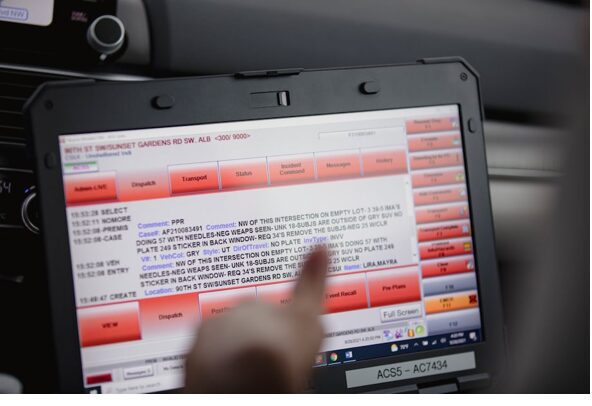

It’s in that context that Adams and his partner, Leigh White, set out one recent afternoon in

a Honda Accord emblazoned with the department’s logo. Their trunk was full of water and

Cheetos; the screen perched on White’s lap, a real-time look at the city’s 911 log, was a litany

of woe: suicide, fight in progress, child neglect, wanted person, missing person.

But their first call was of a sort they get more than any other: a UI, or “unsheltered

individual.” The man at the gas station, a caller reported, was facedown and not moving.

Such “down and out” calls are considered low acuity by the 911 system, and it can take four

to five hours for the understaffed police force to respond. But the Community Safety teams

are typically able to get there within minutes.

“We can take these calls and give people the assistance they need much faster,” said Mariela

Ruiz-Angel, director of ACS. “And that gives police the space to do other things. We don’t

want people to interact with the police unless they have to.”

In this case, time was of the essence: The man was in evident pain, his hands bloodied and

trembling, his body crumpled in on itself beside an empty wheelchair. Adams gave him a

bottle of water but could see the man needed serious medical attention. EMS was called, and

he was soon in an ambulance on his way to a hospital.

The outcome may have been the same had police responded. But Jenny Metzler, chief

executive of Albuquerque Health Care for the Homeless, said the question of who responds

to such calls still matters, given the fears that many who live on the streets have of

interacting with the police.

“There’s so much trauma for people experiencing homelessness. Uniforms and badges can

be triggers,” she said. “However well-intentioned or trained an officer may be, we have a

ways to go before that perception and experience changes.”

In many cases, the ACS response is substantively different from what the police would have

done. Later that afternoon, Adams and White were called to an industrial zone where a man

living out of his truck had allegedly siphoned water and electricity from a nearby business.

Through an unusual glitch in the 911 dispatch system, ACS and police units were both called

to the scene.

To the officers, this was a possible crime to be investigated — and they let the man in the

truck know he could face punishment.

The business is “paying for that water, and now you’re using it,” said one officer, as he

peered out from behind sunglasses. “That’s technically larceny.”

As the officer withdrew to check whether the business owner wanted to press charges, White

approached with a different tack.

“You have a place to go? A home? Do you need resources?” she asked the man, whose face

bore a Band-Aid that barely covered a jagged laceration. “Food? Clothing? A shower?”

“I’m good,” said the man, as he kept a wary eye on the other officer.

Back in the car, White and Adams — both of whom have long experience in behavioral health

services through stints in the corrections, probation and juvenile justice systems — were

frustrated. The man might have needed counseling or treatment or just a place to spend the

night. But any hope of establishing a rapport had been dashed when the officer raised the

prospect of charges.

“If you don’t come off as threatening,” White said, “then people are much more likely to

work with you than against you.”

There is also a significantly lower risk of violence, they said.

One piece of the puzzle

A less confrontational and more compassionate response would have made a difference for

Lucero, the 28-year-old who was shot to death by Bernalillo County sheriff’s deputies, said

her sister, Elaine Maestas. The family received a $4 million settlement in the case, but the

sheriff’s office has denied wrongdoing.

After her sister’s death, which is being investigated by the New Mexico attorney general,

Maestas became an advocate for the sort of approach that ACS embodies. The old system,

she said, didn’t work for anyone.

“We’ve put on the shoulders of officers a job that they’re not equipped to handle, and we’re

risking the lives of loved ones who need our help,” said Maestas, who now works on police

accountability issues at the American Civil Liberties Union.

But Maestas said the new Community Safety Department, however welcome, is only one

piece of a much bigger puzzle as officials seek to redefine how they handle mental health.

New Mexico has some of the worst rates of drug overdose deaths, suicides and mental health-related illnesses in the nation, problems that have been exacerbated since the

previous governor, Susana Martinez, dismantled the behavioral health system amid

allegations that its providers were committing fraud.

“The system is broken,” said Ruiz-Angel, the ACS director. “We try to do what we can, but

there are so many gaps.”

Just how many was laid bare when White and Adams responded to a call at a motel that

serves people receiving housing support and other assistance. The manager had had an

argument that morning with guests who wouldn’t leave, and he wanted help getting them

out.

He called for the police but got ACS instead.

“Whoever you guys are, I’m glad you’re here,” the manager said. “This is a business. I can’t

just let someone stay here forever.”

The couple, it turned out, weren’t the only ones giving him trouble. In rooms across the

motel, set beneath a roaring highway, people were unwilling to check out because they didn’t

know where else to go.

“I tried VIC. They can’t help me,” pleaded the veteran in Room 302, referring to the Veterans

Integration Center. “I tried Goodwill. They can’t help me.”

A woman with a black eye and bruises up and down her legs said the motel, with its dingy

curtains and crumbling concrete, had been like “a resort” but that she needed to be out by

Friday. She asked where she could find a place to stay so she didn’t have to rely on her exboyfriend.

The ACS responders could give recommendations, referrals and words of encouragement,

but not much more.

When Adams and White finally found the couple, it turned out they were already on their

way. They were out of their room, their belongings stashed in a stairwell, along with a pair of

pit bulls. A relative, they said hopefully, would soon pick them up and give them a room — at

least for a little while.

White stepped forward with her usual offer: How could she help? What did they need?

Nothing, the man said. “But thank you for checking on us and making sure we’re okay.”